Exploration of CPTSD: Reparenting and Healing a Traumatized Mind

- Aug 13, 2025

- 8 min read

By Fernando Aguilar

Edited by: Jacinda Taggett

As someone who is interested in becoming a mental health professional, I receive a lot of mental health-related content on social media. When I was scrolling on Instagram, I found a reel that claimed that a bear that was trapped in a cage but had been free was still walking in circles as if it was still stuck in the cage. This was then accompanied with a caption mentioning how this is how people with Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) feel. Wondering what CPTSD was and seeing if the claim was true, I started to do a bit of research on both. What I found was depressing; the bear had been stuck in a small cage with another bear for 20 years before being freed. When the bear was going in circles (as seen in Figure 1), it had been seven years of its freedom from the enclosure at the time. Despite its freedom, the bear’s traumatized brain remains trapped in a time when it was not.

The traumatized bear represents how prolonged trauma, like being caged for twenty years, could fundamentally rewire the way it thinks and behaves. Its actions no longer match its reality but its traumatized mind and conditioned body have yet to register its freedom. It has not mentally repaired from the psychological damage it has endured.

Unfortunately, this appears to be the reality of many people who have experienced many forms of traumatic events: despite possibly being free from a toxic environment or abuser(s), their brain and body continue to relive the trauma. In solidifying the diagnosis of CPTSD, it can directly help address trauma and other co-occurring conditions when it comes to other mental health illnesses and challenges and break the cycle of mental health struggle.

PTSD vs. CPTSD / US vs. Non-US—Why the difference?

PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder)

PTSD was officially recognized in the DSM-III back in 1980 and has evolved when it comes to the definition and diagnosis of PTSD. According to the fifth text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR), the diagnostic protocol now defines PTSD as an individual who must have been directly or indirectly affected by a traumatic event either by personal experience or witnessing the event that involves “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence.” Comparatively, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), the diagnostic manual defines PTSD as an event or events that were “extremely threatening or horrific.” Despite the differences in definition and criteria, the overlapping similarities between the ICD-11 and the DSM-5 include intrusions or re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoidance, and reactivity or sense of threat. A summary comparing both diagnostic criteria can be found in Figure 2.

CPTSD (Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder)

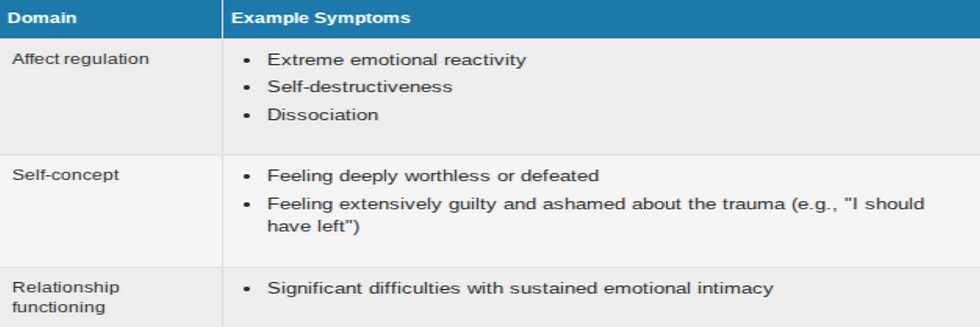

According to the ICD-11, the international diagnostic manual defines CPTSD (Complex PTSD) as having three PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) clusters as well as “three additional clusters that reflect Disturbances in Self Organization (DSO)” (Maercker et al., 2013), as seen in Figure 3. In simpler terms, CPTSD is due to several or repeated traumatic events that are often seen in childhood.

CPTSD and its complexities

CPTSD within itself has several ways of identifying itself, such as Disorders of Extreme Stress Not Otherwise Specified (DESNOS) and Developmental Trauma Disorder (DTD). However, CPTSD helps encapsulate the complexities of trauma. Even so, CPTSD is a relatively understudied diagnosis, as it was formally introduced in 2018 in the ICD-11. CPTSD’s possible existence was being debated as early as when PTSD was introduced in the 1980s, arguing that PTSD alone does not address the complexities of multiple forms of trauma, especially during childhood. Judith Herman, a US-born psychiatrist and trauma expert, was the first to conceptualize the idea of complex PTSD in her book Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror. Even so, the DSM-5 does not currently recognize CPTSD as its own separate diagnosis but rather as a subgroup of PTSD. In contrast, the ICD-11 splits the DSM-5 criteria into 2 groups: PTSD with 3 clusters and CPTSD with the remaining 3 clusters, as seen in Figure 4.

There was a study that aimed to assess whether or not the classification for CPTSD differentiates itself from PTSD using the ICD-11 Trauma Questionnaire (ICD-TQ). Not only were PTSD and CPTSD distinguished as two separate yet similar subgroups, but the study also found that childhood trauma and cumulative stressful life events were significant to CPTSD and were harmful to family and social relationships (Karatzias et al., 2017).

Additionally, there was a higher prevalence of CPTSD in certain demographics, which was found in clinical, domestic, and sexual abuse and military samples. For veterans the extremes of war and a lack of immediate access to mental health resources are factors as to why the PTSD symptoms are so severe. Meanwhile, there was a lower prevalence for CPTSD among emergency and healthcare personnel and the general community due to their accessibility to mental health resources. Despite there being no gender difference when it comes to men and women for CPTSD, women are 1.6 times more likely to be diagnosed with CPTSD in a sample of potentially trauma-exposed samples (Huynh et al., 2025).

Coping with CPTSD

Types of Treatments

When dealing with trauma, it is important to address the trauma(s) of an individual so that their brains register that it is time to heal the mind and body. However, due to how novel the concept of CPTSD is, there are limited updates on the treatment plans for the diagnosis. Even so, there have been pilot studies trying to address the bigger questions surrounding CPTSD.

When it comes to repeated childhood trauma in CPTSD, how can we go back and heal the person's inner child? That is what a pilot study aimed to oversee by practicing the Ideal Parent Figure (IPF) method to treat CPTSD related to childhood trauma. They looked at 17 adults that had a history of childhood trauma with CPTSD symptoms and underwent a 5-week psychotherapy program focusing on the stabilization phase of the three-phase treatment program for CPTSD as well as an 8-month follow-up assessment of stability. There was statistically significant evidence to show that this method of directly addressing attachment helped to decrease CPTSD symptoms (Parra et al., 2017). Given that CPTSD holds multiple forms of trauma, this pilot program, if applied for a longer time, could possibly yield positive results for addressing trauma and CPTSD symptoms.

Speaking of long term, are there any studies that address the possibility of treating CPTSD as a longer-term goal? In yet another pilot study, they took 38 individuals diagnosed with CPTSD and had them participate in a 6-week multimodal psychodynamic inpatient rehabilitation treatment. This treatment focused on four foundations, including how the past and present affect relationships, using internal resources such as the “safe place” imaginative technique, acknowledging emotional dysregulation altered the victim’s way of thinking, and the importance of therapists being aware of their mental health status to avoid burning out or vicarious traumatization (other people’s trauma negatively affects your mental health). The study found that there was a decrease in CPTSD, depression, and anxiety symptoms, as well as an increase in improvement in relationships after a year of the program (Riedl et al., 2025).

Something that had not registered for me was how, outside of telehealth therapy, there is potential to use technology for CPTSD. There was a study on the usage of digital-based interventions (DBIs) for treating mental illnesses post-pandemic. The article compiled 10 papers regarding the efficacy of reducing CPTSD as evidence to see if and how DBIs can treat CPTSD. They explored treatment approaches, the technological modalities used, the level of support needed, targeted symptoms, safety measures, and efficacy of the DBIS. Despite a certain level of efficiency, DBIs are more focused on stabilizing the individual instead of working on their trauma, which is pivotal in treating either form of PTSD and increases the chances of the individual dropping the DBI (Blackie et al., 2024). Even if the results were less than satisfactory, it is always important to try and incorporate technology into mental health spaces and reinforce the importance of tackling the root of the problem rather than trying to pathologize the cause(s).

Reparenting the Inner Child

Whenever I scroll on social media, I am constantly getting many positive affirmations and self-forgiving content on my feed, which has now evolved into reparenting language. For example, instead of punishing yourself for breaking a dish or spilling milk on the floor, you simply tell yourself that making small accidents is just part of being human. This shift in mindset helps to heal the inner child by validating the hurt while telling your inner child what it should have heard growing up.

But when it comes to psychology, what surprised me was seeing how reparenting is viewed in therapy spaces. In a study it brings up an interesting point classifying a therapeutic relationship as an attachment. The paper would then explore how limited reparenting, which is the attachment-informed approach to schema therapy, can benefit a client’s attachment needs. Not only should therapists be aware of their attachment style and how it can shape the therapeutic experience of a client but it also asks therapists with insecure forms of attachment to also seek therapy so as to not compromise their clients’ healing process (Andrioupoulou, 2022).

CPTSD—A new gateway of addressing trauma

Addressing the complexities of trauma in PTSD can help individuals realize the severity of their trauma from a scientific standpoint as well as expand on addressing trauma in itself. Some professionals argue that this new diagnosis would invite more people with CPTSD. That is the point, for only then will more individuals seek the support they need and deserve as well as add value to the argument that society and the systems in place contribute to the production of mental illnesses and worsening conditions. If we factor in racial abuse and homophobic and transphobic laws and rhetoric as examples, it will expose how embedded mental health struggles are in our modern day. The simple step of recognizing CPTSD in the DSM-5 would help bring the US and other countries to work together and figure out CPTSD and how to properly treat it. Trauma will no longer be something taboo but rather something that can be properly explained to improve lives.

References

Sagebrush psychotherapy. (2019). Sagebrush Psychotherapy. https://www.sagebrushpsychotherapy.com/complex-trauma

Huynh, P. A., Kindred, R., Perrins, K., de Boer, K., Miles, S., Bates, G., & Nedeljkovic, M. (2025). Prevalence of Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD): A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatry Research, 351, 116586. Science Direct. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2025.116586

Karatzias, T., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., Hyland, P., Efthymiadou, E., Wilson, D., Roberts, N., Bisson, J. I., Brewin, C. R., & Cloitre, M. (2017). Evidence of distinct profiles of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) based on the new ICD-11 Trauma Questionnaire (ICD-TQ). Journal of Affective Disorders, 207, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.032

Blackie, M., Kathleen De Boer, Seabrook, L., Bates, G., & Nedeljkovic, M. (2024). Digital-Based Interventions for Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Systematic Literature Review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 25(4). Sage Journals. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380241238760

PTSD and DSM-5 - PTSD: National Center for PTSD. (2023, June 9). Www.ptsd.va.gov. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/dsm5_ptsd.asp#one

Treatment (US), C. for S. A. (2014). Exhibit 1.3-4, DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD. Www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK207191/box/part1_ch3.box16/?ref=quillette.com

U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. (2014). Complex PTSD - PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Va.gov. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/essentials/complex_ptsd.asp

TraumaDissociation. (2014). Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Trauma Dissociation.

Riedl, D., Thaler, J., Kirchhoff, C., Kampling, H., Kruse, J., Nolte, T., Campbell, C., Grote, V., Fischer, M. J., & Lampe, A. (2025). Long‐Term Improvements of Complex Post‐Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) Symptoms After Multimodal Psychodynamic Inpatient Rehabilitation Treatment–An Observational Single Center Pilot Study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 81(8), 739–754. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23809

Parra, F., George, C., Kalalou, K., & Januel, D. (2017). Ideal Parent Figure method in the treatment of complex posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood trauma: a pilot study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(1), 1400879. Taylor & Francis Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1400879

Andriopoulou, P. (2022). Healing attachment trauma in adult psychotherapy: The role of limited reparenting. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 23(4), 1–15. Taylor & Francis Online. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642537.2021.2000465

Comments